Information regarding the manifestations and management of ocular mpox infections within NSW.

Background and significance

Since 2022, there has been a global outbreak of mpox which has affected New South Wales and other Australian jurisdictions. Globally, the prevalence of ocular mpox varies greatly depending on the region, with 1% prevalence in Europe and up to 27% prevalence in Africa

1. The complications from ocular mpox can be significant including corneal scarring and vision loss, and therefore prompt diagnosis and management are essential

2.

Presentation

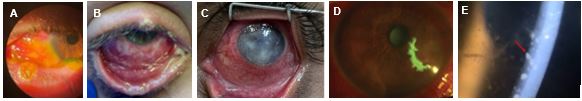

Mpox can enter the eye through autoinoculation and can cause ocular conditions such as conjunctivitis, blepharitis, keratitis and corneal ulcers. It is also more common in young children

2. Examples of these ocular conditions can be see in the clinical images below.

- Membranous conjunctivitis with focal conjunctival erosion

3

- Membranous and mucopurulent conjunctivitis

3

- Keratitis with corneal opacities

4

- Geographical corneal ulcerations

3

- Anterior uveitis with keratitic precipates

4

Testing

Patients presenting with signs and symptoms concerning for ocular mpox should have an eye swab collected and sent for testing. This can be a dry sterile swab (preferred) or a viral eye swab sent in a viral transport media

5. If other viral pathogens are suspected a second swab should be collected and placed in a separate bag

6. Swabs should also be collected from skin lesions and other sites such as rectal and nasopharyngeal swabs guided by relevant symptoms

6. Clinicians should ensure they wear appropriate personal protective equipment when collecting samples including disposable fluid-resistant gown, disposable gloves, face shield or goggles, and a fluid-repellant surgical mask. Consider an N95 mask if the patient also has respiratory symptoms, or if there is a high-risk exposure event including prolonged exposure or aerosol-generating activities

7.

Treatment

According to the World Health Organization, patients with ocular manifestations of mpox are considered to have severe mpox infections, and hospital evaluation and possible admission is warranted

8. Patients should be discussed with Ophthamology at Westmead Hospital. Antiviral medications can be obtained from the NSW Specialist Service for High Consequence Infectious Diseases (or the Infectious Diseases Physician on-call at Westmead Hospital) - see

NSW Specialist Service for High Consequence Infectious Diseases for details

9.

In consultation with the above specialists, the below treatments may be recommended:

- PO Tecovirimat

- Adults 600mg BD PO for 14 days

- Paediatric 13-25kg: 200mg BD, 25-40kg: 400mg BD, >40kg: 600mg BD, with high fat meal

- Should be considered in all patients with severe mpox, which includes ocular manifestations of mpox

2,

10.

- Topical Trifluridine 1%*

- 1 drop every 2 hours whilst awake (maximum daily dose of 9 drops) until the corneal ulcer has re-epithelialised

- Following re-epitheliaslisation, instil one drop 5x per day for 7 days

- It is not recommended to exceed a total duration of 21 days of use due to the risk of corneal epithelial toxicity

- Recommended for mpox keratitis and should be considered in cases of mpox conjunctivitis

2, 11.

Other alternatives may include:

- IV Cidofovir - significant adverse effects including nephrotoxicity and myelosuppression

10

- PO Brincidofovir*

8

IV vaccinia immunoglobulin may be considered on a case-by-case basis (based on evidence from animal models showing reduced corneal scarring)

2.

Topical lubricants and broad-spectrum topical antibiotics (e.g. chlorsig, ocuflox) to prevent secondary bacterial infections in cases with corneal ulcers and/or keratitis.

Topical steroids should be avoided (may prolong the presence of the virus in ocular tissue)

2.

Text alternative

Prevention

Regular hand hygiene and avoidance of rubbing/touching the eye will help prevent autoinoculation of mpox

2. Prophylactic topical trifluridine should be considered in patients with eyelid lesions or children/people not able to follow strict hygiene instructions

2.

Useful resources

References

-

Gandhi, AP, Gupta, PC, Padhi, BK, Sandeep, M, Suvvari, TK, Shamim, MA, Satapathy, P, Sah, R, Leon-Figueroa, DA, Rodriguez-Morales, AJ, Barboza, JJ, Dziedzic, A. 'Ophthalmic Manifestations of the Monkeypox Virus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis'. Pathogens. 2023. 12 (3). Accessed doi:10.3390/pathogens12030452.

-

U.S Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Interim Clinical Considerations for Management of Ocular Mpox. 2024.

-

Pazos, M, Riera, J, Moll-Udina, A, Catala, A, Narvaez, S, Fuertes, I, Dotti-Boada, M, Petiti, G, Izquierdo-Serra, J, Maldonado, E, Chang-Sotomayor, M, Garcia, D, Camós-Carreras, A, Gilera, V, De Loredo, N, Peraza-Nieves, J, Ventura-Abreu, N, Spencer, F, Del Carlo, G, Blanco, J. L. 'Characteristics and Management of Ocular Involvement in Individuals with Monkeypox Disease'. Ophthalmology. 2023. 130, no. 6: 655–58. Accessed doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2023.02.013.

-

Finamor, L. P. S., Mendes-Correa, M. C., Rinkevicius, M., Macedo, G., Sabino, E. C., Villas-Boas, L. S., de Paula, A. V., de Araujo-Heliodoro, R. H., da Costa, A. C., Witkin, S. S., Santos, K. L. C., Palmeira, C., Andrade, G., Lucena, M., de Freitas Santoro, D., da Silva, L. M. P., & Muccioli, C. 'Ocular Manifestations of Monkeypox Virus (MPXV) Infection with Viral Persistence in Ocular Samples: A Case Series'. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2024. Accessed doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2024.107071.

-

Public Health Laboratory Network.

Guidance on Mpox Patient Referral, Specimen Collection and Test Requesting. 2025.

-

New South Wales Health.

Mpox NSW Control Guideline for Public Health Units. NSW Health. 2024.

-

Public Health Laboratory Network.

Mpox (Monkeypox virus infection) Laboratory case definition. 2023.

-

World Health Organization.

Clinical Management and Infection Prevention and Control for Monkeypox. 2022.

-

New South Wales Health.

Information for clinicians treating patients with mpox who require hospitalisation. 2024.

-

Australian Centre of Disease Control.

2024 Mpox Treating Guidelines. 2024.

-

Pfizer.

VIROPTIC ® Ophthalmic Solution, 1% Sterile (trifluridine ophthalmic solution) Physician Prescribing Information. 2018.