On this page

-

Revision history

-

Summary

-

The disease

-

Routine prevention activities

-

Surveillance objectives

-

Data management

-

Communications

-

Case definition

-

Laboratory testing

-

Case management

-

Environmental evaluation

-

Contact management

-

Special situations

-

Appendices

-

Footnotes

NSW revision history

1.0 | 01/07/2013 | - | - | |

|---|

2.0 | 30/11/2015 | Communicable Diseases Branch | Update to ensure consistency with the CDNA Rabies and Other Lyssavirus Series of National Guidelines, v3.0, and the Australian Immunisation Handbook, 10th edition. Provides NSW-specific operational advice, including: factors to consider in risk assessments, afterhours PEP orders, communication, data management and bat testing.

| Approved 21/12/2015 |

|---|

| 3.0 | 08/03/2024 | One Health Branch | Update to ensure consistency with the CDNA Rabies and Other Lyssavirus Series of National Guidelines, v4.0, and the Australian Immunisation Handbook, 10th edition.

Provides NSW-specific operational advice, including: people exposed to "fluid" while near or under where bats are roosting, changes to rabies vaccine and RIG availability and brands, advice for determining appropriate delays in PEP, minimum requirements for data entry, One Health Branch contact details | 17/03/2024 |

|---|

3.1 | 28/03/2024 | CDNA |

Update to countries considered high risk for rabies virus

| 28/03/2024 |

|---|

CDNA National Guidelines for NSW Public Health Units Revision history

1.0 | 6 August 2012 | Rabies and ABLV SoNG working group | Endorsed by CDNA and AHPC |

|---|

2.0 | 22 December 2012 | Rabies and ABLV SoNG working group | Updated to ensure consistency with 10th edition of The Australian Immunisation Handbook |

|---|

3.0 | 6 December 2013 | Rabies and ABLV SoNG working group | Updated to include ABLV in horses |

|---|

| 4.0 | 24 June 2022 | Rabies and ABLV SoNG working group | Updated to ensure consistency with The Australian Immunisation Handbook and in response to World Health Organization position statement |

|---|

4.1 | 28 March 2024 | Interim Australian CDC | Updated to include to include Timor-Leste in the countries for which precautions for both PrEP and PEP should be considered. |

|---|

The Series of National Guidelines (‘the Guidelines’) have been developed by the Communicable Diseases Network Australia (CDNA) and noted by the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee (AHPPC). Their purpose is to provide nationally consistent guidance to public health units (PHUs) in responding to a notifiable disease event.

These guidelines capture the knowledge of experienced professionals and provide guidance on best practice based upon the best available evidence at the time of completion.

Readers should not rely solely on the information contained within these guidelines. Guideline information is not intended to be a substitute for advice from other relevant sources including, but not limited to, the advice from a health professional. Clinical judgement and discretion may be required in the interpretation and application of these guidelines.

The membership of CDNA and AHPPC, and the Commonwealth of Australia as represented by the Department of Health (‘Health’), do not warrant or represent that the information contained in the Guidelines is accurate, current or complete. CDNA, AHPPC and Health do not accept any legal liability or responsibility for any loss, damages, costs or expenses incurred by the use of, or reliance on, or interpretation of, the information contained in the guidelines.

Endorsed by CDNA: 28 March 2024 (minor update not requiring noting by AHPPC)

Noted by AHPPC: 21 April 2022

Released by Health: 28 March 2024

1. Summary

Public health priority

Urgent.

Case management

No known effective treatment. Isolate case with Standard, Contact and Droplet Precautions for the duration of illness. Determine the source of infection.

Contact management

Urgently assess the need for post-exposure prophylaxis in people exposed to mammals (including bats) or confirmed human cases. Use of human rabies immunoglobulin (HRIG) and rabies vaccine is dependent on the type of exposure and prior vaccination.

2. The disease

Infectious agents

Rabies virus, Australian bat lyssavirus (ABLV), and other lyssaviruses such as European bat lyssavirus (EBLV) 1 and EBLV 2, are members of the

Rhabdoviridae family, genus

Lyssavirus. Seventeen closely related but distinct lyssavirus species have been formally recognised[1]. Rabies virus and other lyssaviruses cause the disease rabies[1].

Reservoir

All mammals are susceptible to infection with rabies virus. Dogs are the principal reservoir of rabies virus in developing countries[2]. Other reservoirs and important vectors of rabies virus include wild and domestic

Canidae, including foxes, coyotes, wolves and jackals; bats; cats; monkeys; skunks; raccoons; and mongooses[2]. Other mammals may rarely be infected.

Australia is currently free of rabies in terrestrial (land dwelling) mammals. However, evidence of ABLV infection has been documented in several species of flying foxes (also known as fruit bats) and insectivorous microbats. It is assumed that all Australian bat species have the potential to carry and transmit ABLV. ABLV has not been isolated from bats outside Australia. However, several lyssavirus species have been found in bats in other countries considered free of terrestrial rabies. It is assumed that bats anywhere in the world have the potential to carry and transmit lyssaviruses.

Mode of transmission

Rabies virus is usually transmitted by the virus-laden saliva of an infected mammal introduced via a bite or scratch, or by virus-laden saliva contamination of mucous membranes or broken skin. Person-to-person transmission via saliva is extremely rare and has not been well documented. There have been rare reports of rabies virus transmission by transplantation of infected tissues or organs[3-5]. Aerosol transmission in humans has not been proven in the natural environment but based on animal experiments it remains theoretically possible[6, 7]. Rabies can also be transmitted through neural tissue[5, 8] and a case of perinatal transmission has also been reported[9].

The only three known human cases of ABLV infection occurred in people who had been bitten or scratched by bats[10-12]. It is assumed that the mode of transmission for ABLV and other lyssaviruses is similar to that of rabies virus.

Bat or other animal blood, urine, and faeces are not considered to be infectious[13, 14].

There is no scientific evidence to suggest lyssaviruses (such as ABLV) can be contracted by eating fruit partially eaten by an infected bat.

Incubation period

The incubation period for rabies virus infection is 5 days to several years (usually 2-3 months, rarely more than 1 year)[15]. The length of the incubation period depends on many factors including wound severity, wound location in relation to nerve supply, proximity to the brain, size of inoculum of virus and the degree of protection provided by clothing and other host factors[2, 15, 16]. The incubation period for ABLV and other lyssavirus infections is less certain but is assumed to be similar to rabies virus; the three documented cases of ABLV infection had likely incubation periods of approximately, 4 weeks, 8 weeks and 27 months [10-12].

Infectious period

The infectious period for rabies virus infection has been described reliably in dogs, in which communicability usually commences 3-10 days before onset of clinical signs and persists throughout the course of the illness[2]. The period of communicability of ABLV and other lyssaviruses is not known.

Clinical presentation and outcome

As the clinical disease caused by classical rabies virus and other lyssaviruses appears to be indistinguishable, the term ‘rabies’ refers to disease caused by any of the known lyssaviruses. Rabies is an almost invariably fatal, acute viral encephalomyelitis, even with intensive treatment. Initial symptoms include fever and sensory changes (pain or paraesthesia) at the site of inoculation. Other reported prodromal symptoms include a sense of apprehension, headache and malaise. There are two clinical forms of rabies. Encephalitic or furious rabies presents in about two-thirds of cases, and is characterised by hyperactivity and aerophobia and/or hydrophobia followed by delirium with occasional convulsions[2, 17]. The second form, paralytic or dumb rabies, presents in about one-third of cases, with paralysis of limbs and respiratory muscles with sparing of consciousness. Phobic spasms may be absent in the paralytic form[2]. Death from cardiac or respiratory failure occurs within 7-10 days[15].

Persons at increased risk of disease

The risk of infection after the bite of a rabid animal can range from less than 1% to 60% [18, 19] presumably related to the size of inoculum, severity of bite, nerve density in the area of the bite, proximity of the bite to the central nervous system, vaccination status and immunocompetence[20-22]. People at increased risk of rabies or ABLV infection are those whose occupational, volunteering, or recreational activities put them at increased risk of exposure, i.e. being bitten or scratched by mammals in rabies-enzootic countries or by bats anywhere in the world. Therefore, risk is greatest in those who travel to countries in which rabies is enzootic, and in Australia, in those most likely to come into contact with bat species, including wildlife carers, wildlife officers, veterinary nurses, zoo keepers, wildlife researchers, veterinarians and those who live in areas where bats are common.

Disease occurrence and public health significance

Australia is free from terrestrial rabies. Only two confirmed human cases have been reported in Australia, a 10 year old girl in 1990 who had migrated from Asia, and a 10 year old boy in 1987 who had travelled in Asia[23, 24].

Rabies virus is enzootic in Asia, Africa, North and South America and parts of Europe. Approximately 99% of cases are due to transmission by dogs[25]. Worldwide, it is estimated that dog associated rabies is responsible for more than 59,000 deaths per year with most in Asia (59.6%) and Africa (36.4%) and in poor rural communities[15]. Approximately 40% of cases of rabies occur in children aged less than 15 years[25].

Rabies results in an estimated annual global financial burden of over US$8 billion[15]. Most human deaths follow dog bites for which adequate post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) was not or could not be provided. PEP initiated at an early stage using rabies vaccine in combination with rabies immunoglobulin may be 100% effective in preventing rabies-related deaths.

Rabies is not a listed human disease under the Commonwealth Biosecurity Act 2015but is subject to animal quarantine controls under the Act. The primary concern is the prevention of the introduction of rabies virus to local dog and wildlife populations. State animal authorities are responsible for rabies virus surveillance and preparedness activities, and disease control if the disease were introduced.

Bat associated rabies accounts for a relatively small proportion of rabies globally but is the most common source in the Americas[15]. Small numbers of rabies deaths have occurred following exposure to non-rabies virus lyssaviruses associated with bats including: European bat 1 lyssavirus (2 deaths), European bat 2 lyssavirus (2 deaths), Irkut lyssavirus (1 death), and Duvenhage lyssavirus (3 deaths)[15, 22].

ABLV is unique to Australia and was first identified in 1996 in an encephalitic black flying fox. Three human cases have subsequently been reported, in 1996, 1998 and 2013 with all three cases developing fatal encephalitis after being bitten or scratched by bats[10-12]. To date, virological and/or serological evidence of ABLV infection has been found in all four species of flying foxes found in mainland Australia, and at least seven genera of Australian insectivorous bats[26, 27]. Any Australian bat should be considered a potential carrier of ABLV. Evidence suggests that ABLV prevalence in the wild bat population is low (less than 1%). ABLV infection is more common in sick, injured and orphaned bats, especially those with neurological signs, which are more likely to come into contact with humans[28, 29] The risk of human exposure to ABLV is related to the extent of human contact with Australian bats. In 2013, two horses from the same Queensland property were confirmed to be infected with ABLV. Both horses displayed neurological signs and were euthanised (29, 30)[30, 31]. The risk of secondary transmission to humans is thought to be very low; however, a risk assessment should be conducted following any potential exposure[32].

3. Routine prevention activities

Pre-exposure vaccination (PrEP)

Pre-exposure vaccination (PrEP) with rabies vaccine is recommended for people whose occupation (including volunteer work) or recreational activities place them at increased risk of being bitten or scratched by bats, and, following a risk assessment, those who work in or travel to rabies-enzootic countries. Public Health England maintains a

list of terrestrial rabies risk by country. Although Timor-Leste is not on this list, recent detections of terrestrial rabies with associated human mortalities have occurred on the island of Timor, including West Timor (Indonesia) and Timor-Leste. Precautions including PrEP and post exposure management should also be considered, following a risk assessment, for people who work in or travel to West Timor (Indonesia) or Timor-Leste.

Current groups recommended for pre-exposure vaccination include:

- bat handlers, veterinarians, wildlife officers, veterinary nurses, zoo keepers, wildlife researchers and others who come into direct contact with bats

- laboratory personnel working with live lyssaviruses

- expatriates and travellers (following a risk assessment) who will be spending time in rabies-enzootic areas

- people working with mammals in rabies-enzootic areas[16].

As described in the

Australian Immunisation Handbook, there are two rabies vaccine preparations available in Australia, a human diploid cell vaccine (HDCV) and a purified chick embryo cell vaccine (PCECV)[16].

NSW specific guidance

Since publication of the CDNA SoNG a third rabies vaccine has been made available in Australia, a purified Vero cell rabies vaccine (PVRV). For current information about the vaccines available in Australia, visit the Australian Immunisation Handbook.

Pre-exposure vaccination with rabies vaccine consists of 3 doses on day 0, day 7 and day 21-28. Although not preferred, a shortened schedule can be used if needed but if used a booster is recommended at 1 year if further exposure is expected. For further information see the

Australian Immunisation Handbook[16].

While the intramuscular (IM) route of administration is preferred, the intradermal route may be used as PrEP by suitably qualified and experienced providers as an ‘off-label’ use. If intradermal rabies PrEP is considered, it is essential that:

- It is given by immunisation providers who have expertise in, and regularly practise, the intradermal technique.

- It is not given to anyone who is immunocompromised.

- It is not given to people taking chloroquine or other antimalarials that are structurally related to chloroquine (such as mefloquine) at the time of vaccination and within 1 month after vaccination.

- The immunisation provider discards any remaining vaccine at the end of the session that they opened the vial in (that is, after 8 hours)[16].

Pre-exposure booster doses are not required for anyone who has received three or more previous IM doses of rabies vaccine, if their only exposure risk is travelling to or living in a rabies enzootic area[16]. Booster doses are recommended if there is an ongoing occupational (including volunteer work) exposure risk, on the basis that there may be increased likelihood of an inapparent exposure occurring. See the current online edition of the

Australian Immunisation Handbook including

Booster algorithm for people at ongoing risk of exposure to rabies virus or other lyssaviruses for further information on vaccine administration and booster doses required[16].

Handling bats

Only appropriately vaccinated and trained people should handle bats[33]. Members of the public are strongly advised not to attempt to handle bats (live or dead), but instead contact a wildlife care organisation, wildlife officer or veterinarian if they find a sick or injured bat. If bats must be handled, every effort should be made to avoid being bitten or scratched, including:

- Using appropriate

personal protective equipment (PPE), such as puncture-resistant gloves and gauntlets, long sleeved clothing, safety eyewear or face shield to prevent mucous membrane exposures, and a towel to hold the bat[34].

- For disposal of dead bats, first prod the bat with a long tool to be sure it is dead. Wear gloves and use a tool such as a spade to place the bat in a strong plastic bag, then into a second plastic bag, and dispose according to local council requirements[35, 36].

NSW specific guidance

See the “Testing and specimen submission guidelines – animals” section for further NSW advice on the collection and testing of bats involved in a potential human exposure to ABLV.

Travel advice

Travellers should be advised to avoid close contact with bats anywhere in the world. Travellers to rabies-enzootic regions should also be advised to avoid close contact with wild or domestic terrestrial mammals (especially dogs, cats and monkeys). Travellers should also be advised what to do if bitten or scratched by a mammal while abroad. This advice should include stressing the importance of obtaining as much written detail as possible on any post-exposure management provided overseas. Parents should ensure that their children are careful around mammals as young children are at optimal height for high-risk bites to the face and head. Rabies pre-exposure vaccination (or if appropriate, booster doses) should be advised pre-travel where indicated by a risk assessment, which should include ease of access to PEP and likelihood of interaction with mammals based on type of accommodation and planned activities.

Management of potential human exposure to rabies or other lyssaviruses, including ABLV

(See

Australian Immunisation Handbook:

Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: terrestrial animal exposures and

Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: bat exposures).

NSW specific guidance

Vaccination regimens

In general, the

Australian Immunisation Handbook recommends a modified Essen (4 dose) vaccination regimen for non-immune immunocompetent people with a Category 2 or 3 exposure. The number of doses changes based on the type and category of exposure, prior immunisations, immunocompromise and other factors.

Please note, although the PVRV product information sheet does not provide advice on using a modified Essen regimen, it is appropriate to administer the number of doses recommended in the current Australian Immunisation Handbook.

Definition of potential exposure

- Any bite or scratch from, or mucous membrane or broken skin contact with the saliva or neural tissues of:

- Exposures due to direct contact with bats in situations where bites or scratches may not be apparent (as some bats have small teeth and claws)

- See Unknown bat exposures and Exposures to dead mammals below.

If there are concerns about other potential exposures, expert advice should be sought.

Principles of post-exposure management

Post-exposure management is recommended for any person with a potential exposure. Post-exposure management comprises wound care, administration of a combination of rabies vaccine, and, if indicated, human rabies immunoglobulin (HRIG).

Regardless of previous rabies vaccination, immediate cleansing of the wound is an important measure for minimising transmission risk[16, 33, 37]. Animal studies have shown that immediate and thorough cleansing of the wound reduces the risk of infection[37-39].All wounds should be washed thoroughly for approximately 15 minutes with soap and copious water, as soon as possible after the exposure[15]. A virucidal antiseptic solution such as povidone-iodine or alcohol should be applied[25]. The wound should not be sutured unless unavoidable. If suturing is unavoidable, HRIG, if indicated, should be given prior to suturing[15]. Consideration should also be given to the possibility of tetanus and other wound infections, and appropriate measures taken. In the event of mucous membrane (eyes, nose, mouth) exposure immediately flush with copious water[15].

Rabies vaccine and HRIG (if indicated) should be given as soon as practicable with the degree of urgency based on risk assessment.

Administration of rabies vaccines for PEP by the intradermal (ID) route in Australia is not recommended.

Risk assessment includes consideration of:

- type of exposure (see Table 1)

-

severity (e.g. size and number of wounds) and

location of wounds in relation to nerve centres. Head, face or neck wounds are generally considered a higher risk and should be attended with greater urgency.

-

age of the individual and

reliability of information about the event. Exposure of young children, mentally disabled persons or other circumstances where a reliable history cannot be obtained may necessitate treatment as a category II or III exposure

- prior rabies vaccination and/or antibody status of the individual

-

details about the mammal exposed to, including: the species, risk of rabies in that species and geographic location, the circumstances of exposure (provoked, unprovoked) and behaviour of the mammal. The PEP management pathway will depend on the mammal involved in the exposure. See the following algorithms in the

Australian Immunisation Handbook:

-

time interval since exposure – PEP should be considered regardless of the time interval but may be delayed or discontinued in certain circumstances (see below)

- availability of the mammal for observation or testing (see below).

NSW specific guidance

Egg allergy: Any significant egg allergy would impact vaccine choice for PEP-eligible contacts and should be considered as part of the risk assessment (see advice in the

Australian Immunisation Handbook).

The administration and logistics of providing rabies PEP is resource intensive to the health system and demanding on individuals. In certain low-risk circumstances, ordering and commencing PEP may be delayed, or PEP may be discontinued:

- If a traveller presents 15 days or more (≥15 days) after being bitten or scratched by a domestic dog, in a rabies-enzootic country, and it can be reliably ascertained that the animal remains healthy, then post-exposure rabies management is not required. Note that this recommendation does not apply to exposures to other mammals, including bats.

- If rabies PEP was commenced for a traveller who was bitten or scratched by a domestic dog, in a rabies-enzootic country, and it can be reliably ascertained that the animal remains healthy 15 days or more (≥15 days) after the exposure then rabies PEP may be discontinued[40].

- Bats involved in a potential ABLV exposure in Australia should be tested where the bat is available and testing is appropriate without placing others at risk of exposure. After a risk assessment, in situations determined to be lower risk, commencement of PEP can be delayed for 48 hours post-exposure to enable a result from the bat to be received. In situations determined to be higher risk, or if results are not likely to be available within 48 hours of exposure, then PEP should be commenced. If the bat tests negative, PEP is not required, and may be discontinued if already commenced.

- If the person presents for medical care more than 12 months post exposure then HRIG is not recommended.

- If an extended delay has occurred in reporting, such that it is 10 years or more from exposure, in lower risk exposures it may be appropriate to not provide any PEP.

If a person has received a completed course of PEP by the IM route, which was completed within the past 3 months they do not require any further rabies vaccine doses (or HRIG) and only require wound management.

NSW specific guidance

Considerations around delaying PEP pending bat testing results

Where a risk assessment is being undertaken to decide whether PEP can be delayed until a bat result is received (as per the dot points above), please consider the following definitions:

- high risk exposures may include those that are category 3 and the person:

- has bites or scratches at areas with higher innervation (e.g. head, neck, face or hands)

- has multiple severe wounds

- is an infant or young child with significant wounds

- is immunocompromised

- lower risk exposures may include:

- bite or scratches at areas with lower innervation (e.g. leg, arm, torso)

In instances where bat testing is undertaken and a negative result is received from the Elizabeth Macarthur Agricultural Institute (EMAI), PEP is not required and may be discontinued if already started. PHUs are not required to wait for results from the Australian Centre for Disease Preparedness (ACDP; formerly the Australian Animal Health Laboratory) to make this decision; however, in the unlikely event that ACDP report a result that is discrepant to the findings of EMAI (e.g. a positive immunofluorescence assay), a decision on PEP administration should be made in consultation with the PHU, OHB, EMAI and ACDP.

See the “Testing and specimen submission guidelines – animals” section for further NSW advice on the collection and testing of bats involved in a potential human exposure to ABLV.

Table 1: Lyssavirus exposure categories*

Category I | Touching or feeding animals, licks on intact skin, as well as exposure to blood, urine or faeces** |

|---|

Category II | Nibbling of uncovered skin, minor scratches or abrasions without bleeding |

|---|

Category III | Single or multiple transdermal bites or scratches, contamination of mucous membrane or broken skin with saliva from mammal licks, exposures due to direct contact with bats in situations where bites or scratches may not be apparent**** |

|---|

Source: Modified from WHO[15, 25]

* PEP management pathways differ between terrestrial mammals and bat exposures. To be used in conjunction with: the

Australian Immunisation Handbook,

Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: terrestrial animal exposures and

Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: bat exposures

** Exposures to dead mammals now require assessment regardless of time elapsed since animal death.

*** Management of direct exposure of mucous membrane or broken skin to infected neural tissue should be considered on a case by case basis.

**** Some bats have small teeth and claws, so bites or scratches may not be apparent. See also ‘Unknown bat exposures’.

If there is difficulty in classifying an exposure as either category I or II, or as category II or III, always assign the higher exposure category.

NSW specific guidance

Further advice on ordering PEP in NSW

Doctors should contact their local PHU on 1300 066 055 for advice on potential exposures to rabies or ABLV. PHU staff will help arrange rabies vaccine and HRIG where required. Where indicated, authorised PHU staff can order PEP via the

NSW Vaccine Centre Online Ordering System. Before placing orders, it is critical that PHU staff review the patient’s weight and calculate the amount of HRIG required to avoid unnecessary repeat orders.

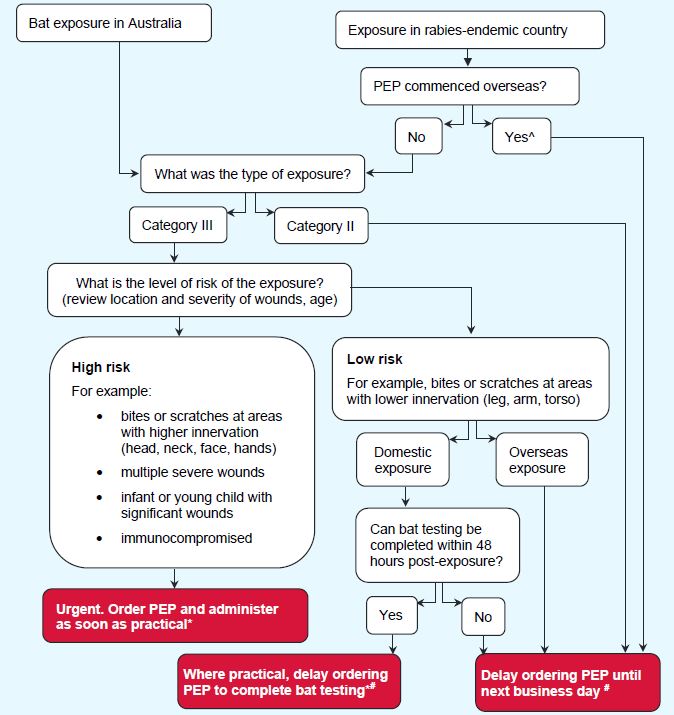

Afterhours orders of PEP from the Vaccine Centre (open Monday to Friday, 8.30am to 4.30pm) can generally be delayed to the next business day, unless the exposure is deemed of a particular high-risk nature and delaying PEP will place additional unnecessary risk on the patient. Consideration should also be given to the longer timeframes needed for PEP delivery in rural/regional areas and whether delayed ordering is appropriate in these settings. All after-hours orders must be approved by the Director of the PHU and no calls should be made after 9.30pm or before 6am. However, the timelines for PEP must be considered on a case-by-case basis, with consideration towards transport requirements (e.g. to rural areas), and delays in PEP are ultimately at the discretion of the treating clinicians and PHUs Director. An algorithm is supplied below to assist PHU staff with decision making (Figure 1).

In instances where an urgent after-hours order is deemed necessary, give consideration to whether:

- the order may be dispatched by the Vaccine Centre the following morning (e.g. in instances where the patient has been asked to return to a clinic the next day with sufficient time for the order to be filled, transported, and administered on that same day),

or

- an immediate dispatch is needed based on the risk assessment.

NSW specific guidance

This algorithm is to assist in deciding the urgency of ordering PEP.

Figure 1: Algorithm for afterhours orders of PEP

If bat exposure was in:

- Australia

- and the type of exposure was

- Category II, delay ordering PEP until next business day #

- Category III, determine the level of risk of the exposure (review location and severity of wounds, age):

- For

high risk. For example:

- bites or scratches at areas with higher innervation (head, neck, face, hands)

- multiple severe wounds

- infant or young child with significant wounds

- immunocompromised

Urgent. Order PEP and administer as soon as practical*

- For

low risk. For example, bites or scratches at areas with lower innervation (leg, arm, torso):

- if bat testing can be completed within 48 hours post-exposure, where practical, delay ordering PEP to complete bat testing*#

- if bat testing can't be completed within 48 hours post-exposure, delay ordering PEP until next business day #

- a rabies-endemic country

- and PEP was commenced overseas, delay ordering PEP until next business day #

- PEP was not commenced overseas, and the type of exposure was

- Category II

- Delay ordering PEP until next business day #

- Category III

- Determine the level of risk of the exposure (review location and severity of wounds, age)

- For

high risk. For example:

- bites or scratches at areas with higher innervation (head, neck, face, hands)

- multiple severe wounds

- infant or young child with significant wounds

- immunocompromised

Urgent. Order PEP and administer as soon as practical*

- For

low risk. For example, bites or scratches at areas with lower innervation (leg, arm, torso), delay ordering PEP until next business day #

^Consider whether HRIG is needed, whether this has been given overseas, and whether delaying ordering PEP would interfere with HRIG administration by day 7.

* While awaiting results, PEP orders and delivery should still be coordinated to occur within office hours wherever possible.

# Timelines for PEP must be considered on a case-by-case basis and delays in PEP are ultimately at the discretion of the treating clinicians and PHUs. Consideration should also be given to the longer timeframes needed for PEP delivery in rural/regional areas and whether delayed ordering is appropriate in these settings. For any outstanding queries, please contact OHB On-call (or Health Protection Medical Officer after hours on-call by phone) to discuss whether or not PEP should be delayed.

Unknown bat exposures

Consider PEP in situations where bat exposure may be difficult to categorise because a person is unaware or unable to communicate that an exposure has occurred following direct contact with a bat. This would be expected to apply only in unique and limited situations, for example a person with an intellectual disability, an intoxicated person or a child. If a wound is apparent or mucous membrane exposure has occurred, manage as per

Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: bat exposures in the

Australian Immunisation Handbook. If there is no wound but direct contact with the bat has occurred, treat as category II or III but do not provide HRIG.

Exposures to dead mammals

A risk assessment, considering the type of exposure, should be conducted for exposures to dead mammals. An in-vivo study of mice inoculated with a laboratory strain of rabies demonstrated that rabies virus remained viable for up to 3 days post-mortem in brain tissue extracted from whole carcasses decomposing at 25°C to 35°C and for up to 18 days at 4°C[41]. Every effort should be made following a potential exposure to have the mammal tested so that unnecessary treatment is avoided. Rabies virus is likely to remain viable for a shorter period in saliva than in brain tissue.

NSW specific guidance

Exposures to dead mammals (continued)

The following additional factors may be considered when assessing the risk of contact to the outside of a dead mammal (as per the

Australian bat lyssavirus – Information for veterinarians guidance):

- ABLV does not survive for more than a few hours outside an infected animal at ambient temperatures but may survive longer in cooler temperatures, including when a carcass is refrigerated.

- Contact with dry surfaces, including intact surfaces of bat carcasses, is unlikely to transmit infection.

The time since bat death, and whether it can be reliably ascertained, should be considered alongside these factors.

People who note being exposed to “fluid” while being present near or under where bats are roosting

In most circumstances, PEP is not recommended. The person should be advised to thoroughly wash the affected part of the body as bat urine or faeces may carry other pathogens. If there is a clear exposure of bat saliva onto a mucous membrane or open wound, manage as per

Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: bat exposures in the

Australian Immunisation Handbook.

This is because there is no known risk of contracting ABLV from bats flying overhead, contact with bat urine, or faeces or from fruit they may have eaten. For classical rabies, non-bite exposures other than organ or tissue transplants have not been shown to cause rabies. After extracting juice, flying foxes (fruit bats) spit out pellets, or 'spats', of chewed and compressed fruit flesh. It is recommended that fruit that has been partially eaten by any animal should be discarded as it could be contaminated by a variety of organisms. Bats are not known to spit out their saliva so this is very unlikely to be the source of the fluid identified by people in the above scenario.

Post-exposure prophylaxis for people not previously vaccinated

Immunocompetent people (excluding those with category I exposures) should receive 4 doses of rabies vaccine by IM injection on days 0, 3, 7 and 14. Where applicable, a single dose of HRIG should also be given as outlined in

Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: terrestrial animal exposures and

Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: bat exposures.

Immunosuppression and immunosuppressive use

Immunocompromised people, whether through disease or treatment, (excluding those with category I exposures) should receive five doses of vaccine IM on days 0, 3, 7, 14 and 28, for both rabies and other potential lyssavirus (including ABLV) exposures. Where applicable, a single dose of HRIG should also be given, as outlined in

Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: terrestrial animal exposures and

Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: bat exposures. A person who is immune-suppressed should have rabies virus neutralising antibody (VNAb) titre checked 2-4 weeks after completion of the vaccine regimen. If the titre is <0.5 IU/mL a further dose of vaccine should be given and serology re-checked 2 to 4 weeks later. Where the titre remains suboptimal (<0.5 IU/mL) an infectious diseases expert should be consulted about the need for further doses[16].

Corticosteroids and immunosuppressive therapy can interfere with the development of active immunity and, therefore, if possible, should not be administered during the period of PEP[16, 42].

NSW specific guidance

Use of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive therapy during the period of PEP should be discussed with the treating clinician to develop a management plan considering risks and benefits.

Pregnancy and lactation

Rabies vaccine and immunoglobulin is safe in pregnancy and lactation[15]. Pregnancy is not considered an immunosuppressive condition in regards to rabies PEP management[15, 43]. Any of the standard regimens as specified in this guideline can be used in pregnancy and lactation[15].

Post-exposure prophylaxis for people previously vaccinated

Immunocompetent people who have sustained a category II or III exposure and:

- who have evidence of a completed recommended pre-exposure prophylaxis regimen (IM or ID), or

- 2 or more previous appropriately spaced doses (IM or ID), or

- who have a previously documented rabies virus neutralising antibody (VNAb) titre of >0.5 IU per mL

are recommended to receive 2 doses of rabies vaccine IM on day 0 and 3[16]. HRIG is not recommended (excluding in immunocompromised persons)[16].

In persons without documented rabies VNAb titres ≥0.5 IU/mL if vaccination status is uncertain, management should occur as for people not previously vaccinated.

People who have only received 1 dose previously as pre-exposure prophylaxis require 4 doses as PEP (similar to those who are unvaccinated):

- If the single dose was given intramuscularly within the 12 months before exposure, no HRIG is required.

- If the single dose was given more than 12 months before exposure, HRIG is required.

- If the single dose was given intradermally, HRIG is required, regardless of when it was given.

If a person has received a completed course of PEP by the IM route, which was completed within the past 3 months they do not require any further rabies vaccine doses (or HRIG) and only require wound management[25].

NSW specific guidance

A completed course of PEP includes documentation of at least 2 doses of pre- or post-exposure prophylaxis rabies vaccine. For more information see the

Australian Immunisation Handbook.

See the following algorithms in the

Australian Immunisation Handbook:

NSW specific guidance

If vaccination status is uncertain, management should occur as for people not previously vaccinated.

Rabies vaccine administration

For adults and children one year of age or older, the rabies vaccine should be administered into the deltoid area, as administration in other sites may result in reduced neutralising antibody titres. In infants under 12 months of age, administration into the anterolateral aspect of the thigh is recommended[16]. The ventrogluteal site is an acceptable alternative for infants. For information on anatomical markers see

Handbook figures.

HRIG use

HRIG, where indicated, should be infiltrated at a dose of 20 IU/kg (round to nearest 0.1mL) in and around all wounds. Ensure a current weight is used. It is imperative that as much HRIG as possible is given in and around the wound/s. The balance of any HRIG dose that cannot safely be infiltrated in and around the wound, or the whole HRIG dose in situations such as mucous membrane exposures (where there is no wound), should be given IM (not into fat) at a site distant (e.g. alternative deltoid, lateral thigh, or gluteal muscle, depending on volume) to that where rabies vaccine is given. If there are multiple wounds HRIG may be diluted in saline to make up an adequate volume for the careful infiltration of all wounds.

The HRIG product routinely used in Australia is typically supplied in 2mL vials containing 150 IU/mL. The following formula can be used to calculate the volume required:

Total HRIG required (mL) = patient weight in kilograms x 20 ÷ 150

NSW specific guidance

The equation above can be further broken down into the below calculations as needed:

Total units required (x) = Patient weight in kg x 20 IU

Volume of HRIG needed to administer in mL (y) = (x) ÷ 150 IU

Total number of vials needed to order (round up where required) = (y) ÷ 2

HRIG is given to provide localised anti-rabies antibody protection while the person mounts an immune response to the rabies vaccine. HRIG should be administered with the first dose of rabies vaccine (day 0). If this is not possible, HRIG can be given up to and including day 7 following the first dose of vaccine, but it should not be given from day 8 onwards as it may suppress the immune response to the vaccine.

If it becomes apparent that HRIG under-dosing has occurred, repeat dosing so that a total dose of 20 IU/kg is given can be considered provided that it is given within the timeframes detailed above.

If significant HRIG overdosing has occurred, as this may interact with the immune response, consider serological testing.

Periods of HRIG shortage

Recurrent shortages of HRIG have occurred in Australia. From time to time, HRIG prioritisation measures may be implemented, at the recommendation of the Communicable Diseases Network Australia. Similarly, special arrangements may be made for use of unregistered HRIG or equine RIG products. In such circumstances, CDNA and jurisdictional disease control units will provide advice on variations to the recommendations provided in these guidelines.

NSW specific guidance

CDNA has previously provided rationing guidance that is no longer current. In the event of a shortage, updated advice would be sought and provided.

Please note, as at February 2024:

- There is no RIG shortage in NSW

- KamRAB is now registered for use in Australia and Imogam is no longer used

Management of PEP in people who have begun prophylaxis overseas

The principle of management of PEP in people who have begun prophylaxis overseas with an appropriate chick embryo–derived or cell culture–derived vaccine is to continue the standard PEP regimen in Australia with either human diploid cell vaccine or purified chick embryo cell vaccine. WHO compiles a list of approved vaccines. Additionally, other chick embryo–derived or cell culture–derived vaccines may be acceptable if the vaccine contains at least 2.5 IU/dose and there is scientific literature demonstrating evidence of an acceptable post-exposure antibody response (≥0.5 IU/mL)[16].

It is preferable to use the same brand of vaccine for the entire course. However, a course of PrEP or PEP can be completed with an alternative rabies cell culture–derived vaccine if necessary[16].

A number of WHO endorsed rabies PEP schedules are used overseas.

Intramuscular WHO endorsed PEP schedules include:

- Zagreb regimen (2 doses on day 0, single doses on days 7 and 21)

- Essen regimen (single dose given on days 0, 3, 7, 14 and either 28 or 30)

- Modified Essen regimen (single dose given on days 0, 3, 7 and 14).

Intradermal WHO endorsed PEP schedules include:

- Institut Pasteur du Cambodge (IPC) regimen (2 doses on days 0, 3 and 7)

- Updated Thai Red Cross (TRC) regimen (2 doses on days 0, 3, 7, and 28).

Table 2 provides recommended courses of action for continuation of PEP in Australia after it has been commenced overseas, for the scenarios most commonly encountered. Where there is good documentation that one or more doses of an appropriate cell culture based vaccine have been given, the schedule can generally be continued, with appropriate realignment.

See Table ‘Rabies vaccines available globally, and compatibility with vaccines registered in Australia’ in current online edition of

Australian Immunisation Handbook.

HRIG should be given if indicated, as outlined in

Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: terrestrial animal exposures and

Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: bat exposures, if RIG (whether equine or human) was not given and it is still within the recommended time frames (See HRIG use section above).

Other situations should be dealt with on a case by case basis. In situations which are not straightforward, seek expert advice on an appropriate schedule, including consideration as to whether testing of rabies VNAb titres is indicated.

Table 2: Post-exposure prophylaxis commenced overseas and recommended completion in Australia

Person received nerve tissue-derived vaccine. | Restart schedule, starting from day 0.

| Administer HRIG if no RIG already given and within 7 days of receipt of 1st PEP vaccine dose.* Do not give HRIG if more than 7 days since 1st dose of vaccine (day 0).* |

|---|

Use of vaccine or RIG is unsure or unknown, or documentation is poor. | Restart schedule, starting from day 0. | Administer HRIG if no RIG already given and within 7 days of receipt of 1st dose of vaccine.* Do not give HRIG if more than 7 days since 1st dose of vaccine (day 0).* |

|---|

Person is immunocompromised, and vaccines were administered ID. | Regardless of number of previous doses, give a 5-dose schedule IM (IM or subcutaneously if human diploid cell vaccine used). Check serology 2–4 weeks after final dose (see Immunosuppression and immunosuppressive use). | Administer HRIG if no RIG already given and within 7 days of receipt of 1st PEP vaccine dose.* Do not give HRIG if more than 7 days since 1st dose of vaccine (day 0).* |

|---|

Scenario is well documented, RIG (equine or human) was given, plus vaccine given either IM or ID (see schedules below for more detail). | Align with nearest due dose and continue schedule. Administer vaccine IM§. | No HRIG is needed. |

|---|

Person received 2 vaccine doses given ID on day 0. RIG (equine or human) may or may not have been administered at same time as 1st dose of vaccine. | Give a further dose IM on day 3, day 7 and day 14§. | Administer HRIG if no RIG already given and within 7 days of receipt of 1st dose of vaccine.* Do not give HRIG if more than 7 days since 1st dose of vaccine (day 0).* |

|---|

Person received 2 vaccine doses given ID or IM on each of day 0 and day 3. RIG (equine or human) may or may not have been administered at same time as 1st dose of vaccine. | Give a further dose IM on day 7 and day 14§. | Administer HRIG if no RIG already given and within 7 days of receipt of 1st dose of vaccine.* Do not give HRIG if more than 7 days since 1st dose of vaccine (day 0).* |

|---|

Person received 2 vaccine doses given ID on each of day 0, day 3 and day 7 (IPC regimen). RIG (equine or human) may or may not have been administered at same time as 1st dose of vaccine. | Give a further dose IM on day 14§. | Do not give HRIG. |

|---|

Person received 2 vaccine doses given IM on day 0. RIG (equine or human) may or may not have been administered at same time as 1st dose of vaccine. | Give a further dose on day 7 and day 21 (Zagreb regimen). | Administer HRIG if no RIG already given and within 7 days of receipt of 1st PEP vaccine dose.* Do not give HRIG if more than 7 days since 1st dose of vaccine (day 0).* |

|---|

* Please consider day 7 as 7x24 hour periods, to account for travel through different time zones.

# See Table 1 and

Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: terrestrial animal exposures and

Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: bat exposures.

§ IM or subcutaneously if human diploid cell vaccine used

4. Surveillance objectives

- To rapidly identify people potentially exposed to rabies virus or other lyssaviruses (including ABLV) and to provide appropriate advice and prophylaxis.

- To monitor the epidemiology of rabies virus and other lyssavirus (including ABLV) infection and potential exposures to better inform prevention strategies, including travel advice.

5. Data management

- Only confirmed cases of rabies virus or other lyssavirus (including ABLV) infection should be reported. Data should be entered within one working day of notification.

- Data on potential human exposures and usage of HRIG and rabies vaccine should be collected and reported. Data on potential exposures and vaccine/HRIG use is entered on jurisdictional and/or the national database maintained by the Commonwealth Department of Health (log in permission provided by Health – contact

CDESS@health.gov.au).

NSW specific guidance

The following should be entered on NCIMS within one working day of notification:

- Confirmed or suspected cases of rabies virus or other lyssavirus (including ABLV) infection

- All potential human exposures notified to PHUs, regardless of whether or not PEP is required, or if PEP has already been completed (e.g. where the full course has been completed overseas or through private purchase).

The event type and condition should be assigned in NCIMS as follows:

Table 3: Classification of potential exposures and cases on the NSW Notifiable Conditions Information Management System (NCIMS)

Exposed to mammal overseas | Contact/exposed person | Lyssavirus - Unspecified |

|---|

Exposed to bat in Australia | Contact/exposed person | Lyssavirus - Unspecified |

|---|

Confirmed human case of lyssavirus/ABLV in Australia | Case

| Lyssavirus - ABL |

|---|

Confirmed human case of classical rabies | Case | Lyssavirus - Rabies |

|---|

When entering potential exposures on NCIMS, the following variables are considered minimum data requirements:

Place of exposure | Both the Clinical and Risk History packages |

|---|

Animal exposed to | Risk history package |

|---|

For bat exposures in Australia: whether bat testing was completed and the test results | Risk history package |

|---|

High risk occupation | Risk history package |

|---|

Occupation | Demographic package |

|---|

Whether PEP was recommended and details on the course of PEP completed | Clinical package

|

|---|

Category of exposure (determined to be category 1, 2 or 3) | Risk history package: “Type of exposure” notes |

|---|

These data are used to:

- Differentiate between potential rabies and ABLV exposures

- Monitor common places and routes of exposure

- Inform public messaging and guidance

- Monitor and manage rabies vaccine and HRIG resources

- Feed into national datasets.

In the event of an outbreak or enhanced public health investigation, additional data points may be required.

6. Communications

Immediately report any suspected exposures to rabies virus or other lyssavirus, and suspected or confirmed case of rabies virus or other lyssavirus (including ABLV) infection by telephone to the local public health unit or state/territory Communicable Diseases Branch. Include information on the possible source/s of infection, other people thought to be at risk and any PEP recommendations.

NSW specific guidance

In NSW, the relevant branch is One Health Branch.

If local transmission of rabies virus is suspected the appropriate state or territory veterinary authority should be contacted urgently or phone the national Emergency Animal Disease Watch Hotline on 1800 675 888 (answered locally in each jurisdiction). If local transmission of ABLV is suspected, communicate with the appropriate state or territory veterinary authority. See

AUSVETPLAN [32].

In the event of locally acquired terrestrial rabies, Health will provide overall national health coordination, provide logistical support to states and territories and activate the National Incident Room. Media releases will aim to reduce the potential for mixed messages and to ensure a common, national message to cases, their families and the general public. The common message will aim to ensure cases and their families receive consistent information about the responsibilities of all agencies involved and the nature of the response.

NSW specific guidance

Doctors should contact their local PHU on 1300 066 055 for advice on potential exposures to rabies or ABLV. PHU staff will help arrange rabies vaccine and HRIG where required.

Any case where rabies or ABLV infection is being considered as part of a differential diagnosis should be immediately reported to the local PHU by telephone. PHU staff will investigate the possible source/s of infection, facilitate laboratory testing, and determine whether others may be at risk of infection who may require PEP.

If local transmission of rabies or other lyssavirus to a terrestrial animal is suspected, the NSW Department of Primary Industries should be contacted urgently by phoning the Emergency Animal Disease Watch Hotline on 1800 675 888. See

AUSVETPLAN.[32]

7. Case definition

Reporting

Only confirmed cases should be notified.

Confirmed case

A confirmed case requires Laboratory definitive evidence only.

Laboratory definitive evidence

- Isolation of lyssavirus confirmed by sequence analysis

or - Detection of lyssavirus by nucleic acid testing.

See the

Department of Health for the current national surveillance case definition. See

Contact management for the definition of a potential rabies/ABLV exposure.

8. Laboratory testing

Testing guidelines – humans

Testing for rabies virus or other lyssaviruses is indicated for persons where rabies is being considered in the differential diagnosis of a clinically compatible illness. No laboratory tests are currently available to diagnose rabies in humans before the onset of clinical disease. Routine serological tests and antigen detection tests cannot distinguish between the different lyssaviruses, but they can be identified by PCR and culture.

In the early stages of disease, saliva and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) can be tested by virus culture and PCR[15]. Antibody testing can also be performed on CSF. Skin biopsy specimens containing hair follicles from nape of the neck can be useful for

ante mortem diagnosis of rabies[15, 17]. A positive serum antibody test is diagnostic of infection with a lyssavirus provided the person has never been immunised against rabies and may assist in the diagnosis of rabies in advanced clinical disease. Any negative test on a symptomatic person is not definitive, as viral shedding in body secretions is intermittent and early tests may be negative for antibody. Therefore, repeat testing is often indicated.

Post mortem, the standard diagnostic techniques include positive fluorescent antibody test (FAT) and nucleic acid test (NAT) on fresh brain smears, and NAT and culture from tissues. Further information is available from the

Public Health Laboratory Network (PHLN) case definition.

Refer to the

Australian Immunisation Handbook for information on routine serological testing for immunity in people who may be occupationally exposed to rabies virus or other lyssaviruses (including ABLV) or who have impaired immunity [16].

The diagnosis of rabies due to rabies virus or ABLV can be confirmed in humans by Queensland Health Forensic and Scientific Services (QHFSS).

Queensland Health Forensic and Scientific Services (QHFSS)

39 Kessels Road

Coopers Plains

QLD 4108

Phone: (07) 3096 2899

Fax: (07) 3096 2878

Testing and specimen submission guidelines – animals

Testing of animals for rabies virus or other lyssaviruses (including ABLV) is indicated in any situation where a person has been exposed to (or is suspected to have been exposed to) the saliva or neural tissue of a potentially infected mammal. A positive result from FAT, virus culture or NAT on fresh brain smear of the animal is diagnostic of rabies.

Where the bat is available and testing is appropriate without putting others at risk, PHU/animal health staff should arrange euthanasia (if required) and testing of bats involved in potential human exposures through usual jurisdictional processes. Public health units should contact their animal health counterparts to assist with organisation of animal testing and/or follow other local protocols as appropriate.

Only appropriately trained and vaccinated individuals, wearing appropriate PPE, should handle potentially infected animals. Members of the public are strongly advised to not attempt to handle bats.

Occasionally, implicated animals may be tested in overseas countries where Australians have been exposed – PHUs should endeavour to liaise with the overseas laboratory or public health authorities in such circumstances to ascertain the result.

If the rabies/ABLV NAT or FAT result from the involved animal is negative, PEP is not required and may be discontinued if it has already commenced.

NSW specific guidance

Please see Principles of post-exposure management for NSW specific guidance on delaying or ceasing PEP based on the results of bat testing following a human exposure.

Collection procedures

PHUs or the public should contact WIRES (1300 094 737) who will collect and transport the bat to a veterinarian who normally deals with wildlife. The veterinarian (or other appropriately trained official) will euthanise the bat, and prepare and package it for transport in accordance with DPI’s

Australian Bat Lyssavirus Guidelines for Veterinarians.

There is no clear responsible party for transport of dead bats for testing. In these circumstances, as with all bat testing related to human exposures, the PHU should assess whether the effort expended to coordinate testing of the dead bat is proportionate to the benefit of the person exposed. Where testing is warranted, transport may need to be arranged via a local veterinarian.

Testing procedure

NSW DPI will pay for testing at EMAI. EMAI will extract the brain and conduct two nucleic acid tests (NAT) for detection of known ABLVs.

EMAI will conduct same-day testing for bats involved in human exposures (incl. weekends), provided that this is clearly communicated by the Emergency Animal Disease Hotline. Otherwise, bat submissions will be treated as routine.

Communication of results

During business hours, test results will be emailed to One Health Branch. Outside of business hours, results are called through to the Health Protection Medical Officer after hours on-call, followed by an email to One Health Branch. The officer on duty will then alert the responding PHU as soon as possible.

Upon receipt, the PHU should confirm that the details of the person exposed match their records. A decision on PEP administration may be made on these results. PHUs should communicate the result and decision to the treating physician, and upload the results to NCIMS. NSW DPI will inform the submitting veterinarian.

Under standard practice, EMAI forwards specimens to ACDP for supplementary testing. ACDP will repeat NAT assays (identical to EMAI’s assays) and conduct serological testing using an immunofluorescence method for confirmation and detection of ‘unknown’ lyssavirus stains. EMAI and ACDP will cover costs of transport and supplementary testing, respectively.

The PHU should not wait for results from ACDP before making a decision on PEP administration, however, the course of action may be altered in the rare instance of a discrepant result. The OHB On Call officer and EMAI are available to assist PHUs with interpreting results or resolving discrepancies, where required. The laboratory can be contacted by telephoning the contact numbers below during office hours.

Reference laboratories

The diagnosis of lyssavirus infection due to rabies virus or ABLV can be confirmed in animals in NSW by the EMAI or ACDP.

- NSW Animal and Plant Health Laboratories

Elizabeth Macarthur Agricultural Institute (EMAI)

Woodbridge Road, Menangle NSW 2568

Phone: 1800 675 623 (office hours only) - Australian Centre for Disease Preparedness (ACDP)

5 Portarlington Road, East Geelong VIC 3219

Phone: (03) 5227 5000

Fax: (03) 5227 5555

Refusal to submit a bat for testing

Where there is a refusal to submit a bat for appropriate testing, the PHU may contact the One Health Branch to discuss further.

In principle, the effort expended to obtain a bat for testing should be proportionate to the benefit of the person exposed.

9. Case management

On the same day of notification of a confirmed case of human disease (or where the clinical picture is highly suspicious of rabies or ABL) begin follow up investigation and notify the state/territory Communicable Diseases Branch.

NSW specific guidance

In NSW, One Health Branch should be notified. During business hours, this should be via phone call to One Health Branch and out of hours should be via the Health Protection Medical Officer after hours on-call.

The One Health Branch or Health Protection Medical Officer after hours on-call can support organising an expert panel discussion of a highly suspicious or confirmed case of rabies or Australian Bat Lyssavirus.

Response procedure

Case investigation

PHU staff conducting the investigation should ensure that action has been taken to:

- confirm the onset date and symptoms

- confirm results of laboratory tests (or request appropriate tests be undertaken)

- seek the doctor’s permission to contact the case (where possible) or relevant care-giver

- interview case (if possible) or carer and determine source of infection - see

Exposure Investigation.

Exposure investigation

Determine the history of contact with bats (in Australia or overseas) or any other mammal in a rabies-enzootic country. If no overseas mammal exposures, or bat exposures then ascertain contact with any mammals in Australia. Determine the type of mammal (and for bats the species if possible), the circumstances and type of exposure, and whether other people or mammals may also have been exposed.

Case treatment

There is no known effective treatment for rabies. A small number of patients have survived rabies following intensive experimental and/or supportive treatment [44-46].

Education

The rabies and/or ABLV fact sheet should be available to carers, and provides information about the nature of infection and mode of transmission. See Appendix 2 - Rabies virus and other lyssaviruses (including Australian bat lyssavirus) fact sheet.

Isolation and restriction

Isolate patient with standard, contact and droplet precautions for the duration of the illness.

Active case finding

Active case finding should occur to determine if any other people or mammals were exposed to the source animal of the case. Exposed people should be urgently assessed for PEP; exposed animals should be managed by veterinary authorities.

10. Environmental evaluation

Any suspected infected mammals, including bats, should be isolated from other animals and humans, and veterinary investigation/management sought including testing where possible, without placing others at risk of exposure. Other measures to reduce the risk of exposure are in the

AUSVETPLAN [32].

Environmental contamination by infected animals is considered negligible; this is based on knowledge of persistence of the classical rabies virus, which is fragile and does not survive for long outside the host[41]. It is readily inactivated by heat and direct sunlight[14]. Bat or other mammal blood, urine, and faeces are not considered to be infectious[13, 14] .

Effective long-term control of lyssaviruses requires vaccination of host-species populations. Control of ABLV through vaccination of bats is not possible, and culling flying foxes would not control or eradicate ABLV. For management of ABLV risk in bats in captivity or care see

AUSVETPLAN [32].

11. Contact management

Identification of contacts

Contact tracing is required to provide advice and PEP to prevent disease in contacts.

Contact definition

Contacts are defined as:

- persons who have been exposed to the saliva or neural tissue of an infectious person through mucous membrane or broken skin contact; or

- persons who have had mucous membrane or broken skin contact to the saliva or neural tissue of infected or potentially infected mammals, usually through bites and scratches, or direct contact with bats in situations where bites or scratches may not be apparent.[1] This includes any bat in Australia or overseas, and any wild or domestic mammal in a rabies-enzootic country.

See ‘Principles of post-exposure management’ above for information about Unknown bat exposures.

Prophylaxis

PEP is recommended for persons who fit the contact definition above. See Management of potential human exposure to rabies or other lyssaviruses, including ABLV and follow up using Appendix 1. Rabies virus and other lyssaviruses (including ABLV) post‑exposure prophylaxis form .

Education

The rabies and/or ABLV fact sheet should be available to inform exposed contacts about the nature of infection and mode of transmission. See

Appendix 2 - Rabies virus and other lyssaviruses (including Australian bat lyssavirus) fact sheet.

Isolation and restriction

None required.

12. Special situations

Domestic mammal exposed to a bat in Australia

Other than bats, two horses and three humans, no other mammals have been documented to have naturally contracted ABLV infection. There is no evidence that ABLV has ever been passed from a wild non-bat or domestic animal to a human, and no definitive evidence that any lyssavirus has ever been passed from a domestic livestock animal to a human. There is, however, a possibility that ABLV spill over to domestic animals could occur occasionally, and a theoretical (although remote) possibility that an infected domestic animal could transmit infection to a human.

Follow-up by PHUs of incidents involving domestic animals which have suffered bites or scratches from bats is not required routinely. If a PHU is informed about a domestic animal exposure from a bat then the owners should be referred to the relevant state or territory animal health authority.

If a domestic animal which has been bitten or scratched by a bat subsequently bites or scratches a human, an expert panel may be convened to advise on management, at the discretion of the managing public health officer. If PEP is to be offered to human contacts in any situation involving domestic animals which have suffered bites or scratches from bats, in the absence of a defined human exposure (i.e. bite, scratch or mucous membrane exposure) to the bat, or laboratory confirmed lyssavirus infection in the animal, an expert panel should always be convened. Consultation with animal health colleagues may be indicated.

Active contact tracing following reports of confirmed ABLV in a bat

All reports of confirmed ABLV in bats received by a PHU, outside of an ongoing case investigation or risk assessment, should be actively followed up to assess the occurrence of any potential human exposures. This may include contacting the veterinarian who ordered the test, the person who submitted the bat, and any individuals who may have handled or come into contact with the bat. PEP should be recommended where appropriate.

13. Appendices

-

Appendix 1 - Rabies virus and other lyssaviruses (including ABLV) post-exposure prophylaxis form

-

Appendix 2 - Rabies virus and other lyssaviruses (including Australian bat lyssavirus) fact sheet

-

Appendix 3 - PHU rabies virus and other lyssaviruses (including ABLV) follow-up checklist

Appendix 1. Rabies virus and other lyssaviruses (including ABLV) post-exposure prophylaxis form

Appendix 2. Rabies virus and other lyssaviruses (including Australian bat lyssavirus) fact sheet

NSW specific guidance

Please refer to the NSW fact sheets:

Appendix 3 - PHU rabies virus and other lyssaviruses (including ABLV) follow-up checklist

Patient ID number: ____________

1. If potential exposure to rabies or other lyssaviruses (incl. ABLV):

Contact the exposed person (or care-giver)

- Identify source and circumstances of potential exposure, including identification of bat species if possible

- Determine if any other persons or animals were exposed to same animal/bat

- Determine if animal/bat available for testing and arrange testing where appropriate

- Review exposed person’s vaccination status and immune competence, and discuss need for post-exposure treatment (PET) and prophylaxis (PEP) and if they have a preferred doctor to manage provision of PET

- Provide with fact sheet: Rabies virus and other lyssaviruses (including Australian bat lyssavirus).

NSW specific guidance

- If eligible for PEP determine if the exposed person has any significant egg allergy

- Confirm risk assessment with senior PHU staff, and determine required timeframe for commencing PEP

Contact exposed person’s doctor

Contact laboratory

Facilitate animal testing, where appropriate. In Australia, this may require liaison with jurisdictional animal health authorities to arrange handling and transport of the animal to a laboratory with capacity to test for lyssaviruses.

NSW specific guidance

To facilitate animal testing in NSW, the PHU (or the public) should contact WIRES (1300 094 737) or their other local wildlife care agency who will collect and transport the bat to a veterinarian who normally deals with wildlife. The veterinarian will euthanise the bat, and prepare and package it for transport in accordance with DPI’s

Australian Bat Lyssavirus Guidelines for Veterinarians.

Other issues

- Enter details of exposure, PET and animal testing onto state/territory communicable diseases branch case report form or into the jurisdictional database as per local protocols.

- Enter exposure data into NetEpi and/or jurisdictional database, as appropriate

2. If human rabies or ABLV case:

Contact the patient’s doctor

- Obtain patient’s history

- Confirm results of relevant pathology tests

- Recommend that the tests be done if needed.

Contact the patient (or care-giver)

- Confirm onset date and symptoms of the illness

- Identify likely source of exposure including type of animal/bat and type of exposure

- Determine if any other persons/animals were exposed to same animal/bat

- Provide fact sheet: Rabies virus and other lyssaviruses (including Australian bat lyssavirus)

Contact laboratory

Obtain any outstanding results

Confirm case

Assess information against case definition

Other issues

- Report details of case to state/territory communicable diseases branch and senior managers as appropriate

- Enter case data onto notifiable diseases database.

14. References

- International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, The Online (10th) Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses: Genus: Lyssavirus. 2019.

- Franka, R., Rabies, in Control of Communicable Diseases Manual, D.L. Heymann, Editor. 2015, APHA Press: Washington.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Investigation of Rabies Infections in Organ Donor and Transplant Recipients --- Alabama, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas, 2004. MMWR, 2004. 53(26): p. 586-9.

- Bronnert, J., et al., Organ Transplantations and Rabies Transmission Journal of travel medicine, 2007. 14(3): p. 177-80.

- Kuehn, B.M., CDC: Rabies transmitted through organ donation. Veterinarians urged to remain vigilant. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Associatation, 2004. 225(4): p. 489-90.

- Davis, A.D., R.J. Rudd, and R.A. Bowen, Effects of aerosolized rabies virus exposure on bats and mice. Journal of infectious diseases., 2007. 195(8): p. 1144-50.

- Winkler, W.G., E.F. Baker Jr, and C.C. Hopkins, An outbreak of non-bite transmitted rabies in a laboratory animal colony. Americal Journal of Epidemiology, 1972. 95(3): p. 267-77.

- McLaws, M. and E. Galanis, Animal bites and rabies management. British Columbia Medical Journal, 2017. 59(3).

- Aguèmona, C.T., et al., Rabies transmission risks during peripartum – Two cases and areview of the literature. Vaccine, 2016. 34: p. 1752-7.

- Hanna, J.N., et al., Australian bat lyssavirus infection: a second human case with a long incubation period. Medical Journal of Australia, 2000. 172(12): p. 597-9.

- Francis, J.R., et al.,

Australian bat lyssavirus in a child: the first reported case. Pediatrics, 2014. 133(4): p. e1063-7.

- Samaratunga, H., J.W. Searle, and N. Hudson, Non-rabies Lyssavirus human encephalitis from fruit bats: Australian bat Lyssavirus (pteropid Lyssaviurs) infection. Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology, 1998. 24: p. 331-5.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

How is rabies transmitted? 2019 11/06/2019 [cited 2019 13/09/2019]; Available from:

https://www.cdc.gov/rabies/transmission/index.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Frabies%2Ftransmission%2Fexposure.html.

- Manning, S.E., et al., Human rabies prevention - United States, 2008: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR, 2008. 57(3).

- World Health Organization,

WHO Expert Consultation on Rabies: Third Report. 2018, World Health Organization.

- Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation,

Rabies and other lyssaviruses, in

Australian Immunisation Handbook2018, Australian Government Department of Health.

- Jackson, A.C.,

Rabies. Neurologic Clinics, 2008. 26(3): p. 717-26.

- Di Quinzio, M. and A. McCarthy,

Rabies risk among travellers. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 2008. 178(5): p. 567.

- Presutti, R.J., Bite wounds. Early treatment and prophylaxis against infectious complications Postgraduate Medicine, 1997. 101(4): p. 246-52, 254.

- Hattwick, M.A.W.,

Human rabies. Public Health Reviews, 1974. 3(3): p. 229-74.

- Neilson, A. and C. Mayer,

Rabies prevention in travellers. Australian Family Physician, 2010. 39: p. 641-5.

- Warrell, M.J. and D.A. Warrell,

Rabies and other lyssaviruses. Lancet, 2004. 363(9413): p. 959-69.

- Dunn, K., et al.,

Imported human rabies--Australia, 1987. MMWR, 1987. 37(22): p. 351-3.

- Bek, M.D., et al.,

Rabies case in New South Wales, 1990: public health aspects. Medical Journal of Australia, 1992. 156(9): p. 596-600.

- World Health Organization,

Rabies vaccines: WHO position paper - April 2018. Weekly epidemiological record, 2018. 93: p. 201-20.

- Prada, D., et al.,

Insights into Australian bat lyssavirus in insectivorous bats of Western Australia. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 2019. 4(1): p. 46.

- Field, H.E., Evidence of Australian bat lyssavirus infection in diverse Australian bat taxa. Zoonoses public health, 2018. 65(6): p. 742-8.

- Barrett, J.,

Australian bat lyssavirus, in

School of Vetinary Science. 2004, University of Queensland.

- Wildlife Health Australia,

ABLV Bat Stats: Australian Bat Lyssavirus report - December 2020. 2020, Wildlife Health Australia.

- Annand, E.J. and P.A. Reid, Clinical review of two fatal equine cases of infection with the insectivorous bat strain of Australian bat lyssavirus. Australian Veterinary Journal, 2014. 92(9): p. 324-32.

- Shinwari, M.W., et al.,

Australian bat lyssavirus infection in two horses. Veterinary microbiology, 2014. 173(3-4): p. 224-31.

- Animal Health Australia,

Response strategy: Lyssavirus (verion 5.0). Australian Veterinary Emergency Plan (AUSVETPLAN). 2021: Canberra, ACT. See

https://animalhealthaustralia.com.au/ausvetplan/.

- NSW Government Department of Primary Industries,

Primefact 1541: Australian Bat Lyssavirus guidelines for veterinarians, Animal Biosecurity NSW Government Department of Primary Industries, Editor. 2019, NSW Government.

- Wildlife Health Australia,

Personal protective equipment (PPE) information for bat handlers. 2020, Wildlife Health Australia.

- NSW Government Department of Primary Industries,

Bats and Health Risks, in

Primefact. 2019.

- Barrett, J.,

Australian bat lyssavirus: information for veterinarians. 2020, Biosecurity Queensland, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries.

- Kaplan, M.M., et al.,

Studies on the local treatment of wounds for the prevention of rabies. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 1962. 26: p. 765-775.

- Rupprecht, C.E., C.A. Hanlon, and T. Hemachudha,

Rabies re-examined. Lancet, 2002. 2(6): p. 327-43.

- Dean, D.J., G.M. Baer, and W.R. Thompson,

Studies on the local treatment of rabies-infected wounds. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 1963. 28(4): p. 477-86.

- Tepsumethanon, V., et al.,

Survival of naturally infected rabid dogs and cats. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2004. 39: p. 278-80.

- McElhinney, L.M., D.A. Marston, and S.M. Brookes,

Effects of carcase decomposition on rabies virus infectivity and detection. Journal of virological methods, 2014. 207: p. 110-3.

- Turner, G.S., Recovery of immune responsiveness to rabies vaccine after treatment of mice with cyclophosphamide. Archives of virology, 1979. 61(4): p. 321-5.

- Kourtis, A.P., J.S. Read, and D.J. Jamieson,

Pregnancy and infection. New England Journal of Medicine, 2014. 370: p. 2211-8.

- Willoughby, R.E.J., et al.,

Survival after treatment of rabies with induction of coma. New England Journal of Medicine, 2005. 352(24): p. 2508-14.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

Recovery of a patient from clinical rabies - California. MMWR, 2011. 61(4): p. 61-5.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

Presumptive Abortive Human Rabies - Texas, 2009. MMWR, 2010. 59(7): p. 185-90.